February 3, 2022

By Nicolette Foss

In the modern music genres of today, there is no doubt the hammered dulcimer is pretty obscure. Most people will look at you blankly, scratch their head and say, “Hammered dulcimer, what’s that?”

But believe it or not, the hammered dulcimer is well known in certain pockets of the world. It shares an extensive family tree with similar instruments that have a rich history and vibrant communities of players just like you.

In this article, we will take a deep dive into these instruments: the dulcimer, salterio, hackbrett, cimbalom, santur, yangqin, and khim. We will touch on the history and musical traditions of their past, today’s styles, as well as peek at the instruments’ wave of the future.

Hammered Dulcimer/Dulcimer

United States: The hammered dulcimer immigrated along with the early settlers to America in the early 1700s. Back then you may have heard it called a whamadiddle or lumberjack’s piano. The instrument can have either chromatic or diatonic tuning systems. It ranges in many sizes featuring its characteristic trapezoidal shape, and rests on a dulcimer stand. There have been phases of popularity over the years, including hammered dulcimer music genres like celtic, hymns, polkas, waltzes, and even modern rock and pop songs.

And the future looks bright for the hammered dulcimer. We have been developing a style of the electric hammered dulcimer to blast us into the modern technological age!

Canada: The hammered dulcimer also spread throughout Canada with the early settlers. However, for over 100 years many players in Western Canada play the Ukrainian tsimbaly. More on that later!

United Kingdom: If we trace the roots of the North American hammered dulcimer, we travel to the UK where its ancestors can still be found in Scotland, East Anglia, Birmingham, and London. The East Anglian dulcimer, a descendant of the Italian salterio, is simply called “dulcimer”. This is because there does not need to be a distinction from the Appalachian dulcimer (aka lap, plucked, or mountain dulcimer) as in the US.

A surge in popularity in the UK occurred between 1850 to 1930, when most of the instruments were made. East Anglian dulcimers are known for their beautiful black paint with gold filigree decorations and movable individual “chessman” bridges. The cane hammers are bent and bound with wool.

Ireland: Though Irish folk music is a huge part of our repertoire for the hammered dulcimer here in the US, little is known about the Irish instrument’s history. We do know that along with the harp and pipes, the hammered dulcimer (“teadchlar” in Irish) was popular in Ireland in the 17th century. Additionally, the timpan or tiompan (thought to be a psaltery) were mentioned in old stories as far back as the 6th century AD and were said to be played by faeries.

Salterio

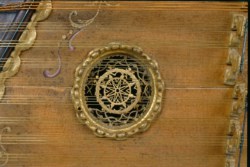

“File:Giovanni Battista Dall’Olio, Salterio, 1764, Museo Civico di Modena, part.jpg” by Archivio fotografico del Museo Civico del Modena is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The salterio is one of the less prominent forms of the hammered dulcimer in the modern age. In Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, the name salterio was used to describe two kinds of zithers: the hammered dulcimer and the psaltery. Definitions of these two instruments can be hazy and confusing. Typically (not always), the hammered dulcimer is a string instrument hit with hammers, while a psaltery is plucked.

Italy: The salterios of the 18th century in countries like Italy and Spain were played by the upper-class aristocracy for composed sinfonia or sonatas. Dukes, counts, countesses, priests, nuns, and cardinals were all lovers and players of this instrument. Ethereal salterio music rang out in churches, theaters, and private palazzi.

The salterios of Italy are typically quite beautiful due to their high-class players, often displaying gilded features and ornamental designs. The instrument is fully chromatic with up to five bridges and can have up to eight strings per course. Nowadays salterios are hung up in museums, cherished in private collections, and played by a select few professional musicians such as Franziska Fleischanderl.

France: The salterio of France was called doulcemèr (derived from Latin dulce melos for “sweet sound” or “lovely sound”) or tympanon. Like the salterio of Italy, the doulcemèr went through a short trend in the 17th and 18th centuries. The nobility were the main players of the doulcemèr, but the trend quickly disappeared during the French Revolution when the instruments were seized.

Mexico: The salterio of Mexico, or salterio Mexicano, is related to the psaltery of the 16th century. The instrument arrived along with the Spanish conquistadors and became a part of Mexican culture. It has five bridges of varying sizes, and courses are double or triple-stringed. There are tenor, soprano, or requinto varieties. The Mexican salterio is placed in the lap and plucked with plectrums (metal picks attached to the index finger on each hand). It is still played occasionally in live performances today. Here is a rendition of a traditional mariachi song, “Las Bicicletas”:

Hackbrett

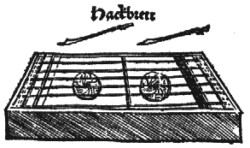

1551 Hackbrett. Sebastian Virdung; uploaded by de:User:Matthias.Gruber, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The hackbrett, a struck string instrument, was an evolution of the string drum and doulcemèr in Germanic countries. The word hackbrett means “chopping board” in German, referring to the striking of hammers resembling the chopping meat on a cutting board. The earliest mention of the instrument was 1447 in Zurich, Switzerland in the books of the town council:

“It happened that Ackli played (struck) the Hackbrett in the night, neither pleasing nor disturbing anyone.”

The hackbrett seemed to have a mixed reception:

- Abraham A Sancta Clara, wrote in 1699 in Etwas für alle: “The country cook plays her Hackbrett so prettily that the gods prefer it even to Apollo’s lyre.”

- In 1713 by Mattheson: “The trifling Hackbrettes (apart from the big ones with gut strings called Pantalon, which is highly privileged) should be nailed up in houses of ill-repute.”

- Of the hakkebord on an anonymous Dutch engraving of that era: “I love my Hakkebord, as much as one can love anything. Yes, I love it a thousand times more than many a man is loved by his wife, though they reflect one another, Yes I will exchange this sound for neither wife, dish, tobacco nor jug.”

Although the instrument was featured in classical music such as the opera and sinfonia (Christoph Willibald Gluck includes two parts for hackbrett in his opera Le cadi dupé of 1761 and Leopold Mozart in his Sinfonia in D Major Le peasant wedding of 1755), it was played mostly in alpine regions and has become a folk instrument over time. The hackbrett comes in various sizes and shapes, including trapezoid, half-trapezoid, rectangle, and with and without soundhole decor.

German hackbrett. photozou: 白石准, CC BY-SA 2.1 JP <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.1/jp/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons

Austria: The Austrian hackbrett has three varieties:

- The Styrian hackbrett, or Steirisches hackbrett, has a diatonic tuning. It has 116 strings in ⅔ proportion. This means the root note is on one side and the fifth is on the other as in our modern American hammered dulcimers. The instrument is played with a few bass pedals and used as a rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment for folk dance music.

- The East Tirol hackbrett, or Osttiroler hackbrett, is also a diatonic tuning but is smaller than the Styrian. It has 72 strings and smaller additional bridges (called “chessboard pawns”) that are removable, which allows control of the raising or lowering of notes by a semitone.

- The Salzburg hackbrett, or Salzburger hackbrett, has chromatic tuning and 128 strings. The strings are only struck on one side of the bridge, similar to the Indian santoor. This is a very heavy instrument with a steel structure (38 kg), and the body is reinforced by iron bars. The hammers are covered with felt to make a softer sound. This variation is the most modern rendition of the hackbrett, created in the 1930s to play Stubenmusik (or parlor music), a form of Alpine folk music.

Switzerland: The Swiss hackbrett has two varieties:

- The Appenzell hackbrett, or Appenzeller hackbrett, is the most well-known hackbrett today. This instrument has chromatic tuning with bridges dividing 125 strings into fifths and sixths. There are 25 courses of 5 strings. Like the Romanian cimbalom or Greek santouri, there may be specialized mini bridges. Typically the hackbrett is played along with an accordion, fiddle, and double bass quartet. However, the instrument is beginning to evolve for a new generation. Check out this video about the Appenzeller hackbrett’s past and future:

2. The Valais hackbrett, or Walliser hackbrett, is very similar to the Osttiroler hackbrett of Austria. The instrument has a clever mechanism that allows the possibility to shorten the length of all sides so they sound a semitone higher. This means you can play in all keys or even chromatically! It is bigger than Osttiroler with 84 strings but smaller than the Appenzeller hackbrett with fewer courses and strings.

German Americans: A version of the German hackbrett has ended up right here in our own backyard. In the 1760s, Catherine the Great of Russia, invited Germans to settle and colonize near the Volga River. Volga Germans (Volksdeutsch or Volga Deutsch) living in western Russia in the late 1800s then migrated to the high plains of the US: Northern Colorado, Western Nebraska, and Southeastern Wyoming. During World War I when Germans were not well-received, they changed their names from Deutsch to Dutch. However, these Germans were able to hold onto their culture and language while living in Ukraine and did the same when they immigrated to the US. Even though the hackbrett lost popularity in Germany, the culture still lives on in the Volga Germans.

The Dutch Hop is a type of dance and style of music that the Volga Germans brought along with them. These dances are mostly polkas, and still a very important part of their culture. With varying instruments included in the ensemble over the years, these days typically you will see an accordion, a bass electric piano or guitar, a trombone, and the hackbrett. The dancers add a bounce to their steps, and a little hop or stomp addition to traditional polka dancing.

Belgium: hakkebord

Sweden: hackbräde, hammarharpa

Netherlands: hakkebord

Norway: hakkebrett

Denmark: hakkebræt

Cimbalom

Concert cimbalom. User:Kar Mester at hu.wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The cimbalom, or concert cimbalom, is a descendant of the hackbrett. Classical composers like Zoltán Kodály, Igor Stravinsky, and Pierre Boulez have all used this instrument in their music. A more recent example of its use is by the Blue Man Group.

Hungary: The concert cimbalom was a variation created by V. József Schunda in 1874 in Budapest. Schunda manufactured over 10,000 of his instrument and it soon became popular with the bourgeoisie and Romani (Gypsies) alike.

Cimbalom. “File:Hungary-0223 – Cimbalom (7338659240).jpg” by Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Before the concert cimbalom was developed, the folk instrument had been played on a barrel or a table. Schunda’s model was built with four detachable legs due to its large size. It also has a built-in damper pedal. It is struck with sticks wound with cotton on the tips to produce a soft, ethereal sound. The treble strings, made of steel, are grouped in courses of four strings. The bass strings are copper wound and have courses of three strings. This is the classical style of the concert instrument. However, there are other variations that may have different tuning systems, lack dampers, and are not heavily constructed but still called cimbalom.

Schunda concert instruments are fully chromatic with no duplicated notes. The tuning system for these cimbaloms has a pitch range of four octaves plus a major third. This extends from C to e′′′ on the Helmholtz pitch notation. Since then, however, modern instruments now have a pitch range that can extend five fully chromatic octaves: from AA to a′′′. These makers produce a wide variety of cimbaloms, from the classic cimbalom to its smaller versions, to even smaller, more portable versions.

Its 19th-century popularity spread across the Austro-Hungarian Empire by way of Jewish and Roma musicians. From as far back as the 16th century, klezmer music has been an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. The theme of the music is typically dance tunes, melodies, and improvisations played for weddings and social events. The small ensemble including the smaller cimbalom (tambal mic) was favored by Roma musicians and originated from the klezmer style.

Both the folk and concert varieties of the cimbalom landed in countries like Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Slovakia, Moldova, Belarus, and Ukraine, where the culture has held and it is still played today. The instruments that were played differed in many ways, however, such as size, tuning, amount of strings, as well as the way of holding and playing the hammers.

The Budapest Gypsy Symphony Orchestra is a famous orchestra group made up of Hungarian Romani (Gypsy) musicians, including six cimbalom players. The group was formed in 1984 when the Primas (first violin and leader) Sándor Járóka died. He was known as “The Primas of kings and the king of Primases”. Roma musicians gathered and played a somber elegy by his graveside, and this is how the group began.

Ukraine: The Ukrainian tsymbaly (цимбали) has courses of between three and five strings, as well as bass strings that may have one to two strings wrapped. Shorter hammers are used compared to the cimbalom hammers, but not still not as short as those used by the tsymbaly players of Belarus. These hammers are also wrapped with leather, providing a softer sound.

The main popularity of the instrument rose in the Carpathians and Southwestern Ukraine especially with the Hutsul and Bukovinian people. It was also found in Boikivshchyna, Transcarpathia, Podolia, Bessarabia and Eastern Ukraine. Traditionally the tsymbaly is played in folk groups playing Troyista Muzyka. The ensemble usually consists of three instruments including the tsymbaly, violin, sopilka (fipple flute), bubon (similar to a tambourine), or basolia (similar to cello).

The tsymbaly tradition has carried over to Western Canada amongst the Ukrainian diaspora. But in addition to the traditional Troyista Muzyka ensemble, they are played alongside electric guitars, synthesizers, violins, drums, and accordions. In places like Alberta, you can hear tsymbaly played at weddings, dances, competitions, festivals, and in recorded music. These folks capture the essence of the Old World in their local music scene.

Tsymbaly. “Roman Kumlyk The Owner Of The Museum Of Musical Instruments And Hutsuls Lifestyle In Verkhovyna (Ukraine)” by MariyaZ is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Variations of tsmbaly:

- Hutsul tsymbaly: This instrument is so small it can be carried, and is held by a strap around the musician’s neck and rests against their waist. The Hutsul tsymbaly typically has 12-13 courses of strings.

- Semi-concert tsymbaly: Manufactured from 1950 to 1986 by Chernihiv Musical Instrument Factory. The instrument came in three sizes: prima, alto, and bass. This type of tsymbaly was the reason for the instrument’s popularity in Eastern Ukraine in the post-war years. However, the preferred choice of professional performers has since shifted back to the original concert cimbalom.

- Concert cimbalom: This is the same variation created by Schunda, and has replaced some of the smaller tsymbalys used in orchestras. However, some variations were called concert tsymbaly and had two pedals, and were slightly smaller than the concert cimbalom from Hungary. It still had the same four-octave range, however. Most Ukrainian folk instrument ensembles and orchestras of today like the Orchestra of Ukrainian Folk Instruments and the State Bandurist Capella usually have two concert cimbaloms.

Belarus: The Belarusian tsymbaly or cymbaly varies from the concert cimbalom in both timbre and size. Belarusian tsymbaly also tend to be without dampers because hands and fingers are used to dampen the strings instead. The tsymbaly is called the instrumental voice of Belarus.

A good-sounding tsymbaly instrument is carefully crafted by its maker. Each master has his own way of choosing the right spruce for their tsymbaly. One may choose the spruce that grows in the sun, producing wood with a brighter color. Another will look for spruce with slower growth and will not grow higher than 15 meters and more than 20 cm thick. Others will knock on the trunk of the tree and listen carefully for the right sound.

The number of strings in a course was increased from four to eight to compete with the sound of the more recent addition of violins in bands. Kruchki (or miniature hammers) are held characteristically between the index and middle finger and have a distinctive curved hook shape.

The Zhinovich National Academic Folk Orchestra of Belarus, named after musician Joseph Iosifovich Zhinovich in 1930, is the oldest musical collective in the country today. This orchestra laid the foundation for the reconstruction of the national folklore instrument, the tsymbaly. It expanded its range with a concert band, opened tsymbaly classes at the Conservatory, and now has over 2,000 compositions in its repertoire. These include Belarusian folk songs and dances, original compositions of composers of Belarus, Russian and foreign classics, music of current composers, and popular music of today.

Russia: цимбалы, dultsimer (дульцимер)

Latgalia: cymbala

Latvia: cimbole

Lithuania: cimbalai, cimbolai

Poland: cymbały

Croatia: cimbal, cimbale, cimbule

Serbia: цимбал (tsimbal)

Slovenia: cimbale, oprekelj

Czech Republic: cimbál

Slovakia: cimbal

Moravia: cimbalom

Romania: ţambal

Israel: דולצימר פטישים

Santur

Santur. “File:Santur1.jpg” by allauddin is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The santur has Persian origins, but is a direct descendant of the qunan and earliest psalteries. In our previous article “Where Did the Hammered Dulcimer Originate?”, we discussed the varying possibilities of the original hammered dulcimer. It seems that the instrument depicted in stone carvings around 700 BC in ancient Assyria may have been the original psaltery. This then possibly led to the evolution of the Persian santur as well as other versions in the Middle East.

Iran: The santur itself originated in Persia or what is now known as Iran around 900 AD. It was made from tree bark, stones, and strung with goat intestines– a far cry from the Persian santur of today!

The instrument itself ranges about three octaves and courses of four strings. The strings for the right hand are made of either brass or copper, and the left-hand strings are steel. The Persian santur has a diatonic tuning, with ¼ tones that are designated into 12 modes, or dastgahs, which makes up the classical music of Persia called the Radif.

The mezrabs (hammers) are oval-shaped and held between the index, thumb, and middle fingers. They are either a simple piece of wood or are tipped with velvet.

Iraq: The Iraqi santur (or santour, santoor) is made of walnut, and has a total of 92 strings, either steel or bronze. The 23 sets of courses are made of four strings each, and struck with hammers called midhrab. The notes extend from lower yakah (G) up to jawab jawab husayni (a) and is fully chromatic.

The bridges are called dama, meaning chessmen in Arabic, because they look like pawns. In the standard santur, some of the bridges are movable: B half flat qaraar, E half flat, and B half flat jawaab. This instrument is played not only in Iraq, but also in Syria, India, Pakistan, Turkey, Iran, Greece (the Aegean coasts), and Azerbaijan.

Along with the Iraqi spike fiddle called the joza, the santur is used in the classical Maqam al-iraqi musical tradition. Watch this interesting performance as Iraqi-American Amir El Saffar explains the Maqam, plays the santur, and sings:

India: The santoor of India is said to be a variation of the Iranian santur, referred to as Shatha Tantri Veena (100-stringed instrument) in Sanskrit texts. It has 100 strings and has been found in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir since ancient days.

The Indian santoor of ancient times was played in a style of classical music called Sufiana Mausiqi, which means mystical music. This style of music was used as an accompaniment to Sufi hymns, and also a dance called Hafiz Nagma. The female dancer, “Hafiza” would represent the meaning of the song through various hand gestures and movements of the body.

Jonlut, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

This dance form, as well as Sufiana Mausiqi, is now out of practice.

The mezrab (or hammers) are lightweight and held between the index and middle fingers. There are two sets of bridges, with notes ranging over three octaves. Usually, the santoor is made out of walnut or maple, but unlike our hammered dulcimer has more of a rectangular shape.

A santoor player will sit in an ardha-padmasana asana, and will place the instrument in their lap to play. Since no dampers are used, a free hand will dampen notes instead.

Greece: santouri

Turkey: santur

Yangqin

China: There are several competing theories of how the dulcimer got to China:

- By land: It is possible it arrived through the Silk Road from the Middle East. The santur may have traveled its way over to China the many years it has been around.

- By sea: Another possibility is through the seaport at Canton/Guangzhou from a Portuguese, English, or Dutch trading ship. After the 16th century, trade developed between the Chinese and Europeans. A dulcimer player may have come on one of these ships to play for the locals.

A yangqin player. File:扬琴 Янцинь.jpg” by Nikolaj Potanin from Russia is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The term yangqin (or yang quin, yang ch’in) was once written as “洋琴”, which meant “foreign zither”. However, over time the first character was changed to “揚”, which means “acclaimed”. Today the yangqin is sometimes referred to as the “Chinese piano” because it plays an integral role in accompanying string and wood instruments.

Traditionally the yangqin has bronze strings, though older instruments actually used silk. More modern yangqin since the 1950s have steel alloy strings (in conjunction with copper-wound steel strings for the bass notes). There are usually 144 total strings, with up to five strings per course.

There are four to five bridges on a yangqin: a bass bridge, right bridge, tenor bridge, left bridge, and chromatic bridge. It is played by striking the strings to the left of the bridges, except for the chromatic on the right. The strings on the left bridge can be struck on both sides. Typically arranged chromatically with a range of just over four octaves. Middle C is the third course from the bottom on the tenor bridge. When playing traditional Chinese music, musicians will use the jianpu notation system instead of Western staff notation.

traditional yangqin hammers

The hammers are made of flexible and lightweight bamboo and have rubber tips. You can play them two ways; with the rubber side for a soft sound, or with the bamboo handle for a crisper tone (the pointed ends can also be used to pluck the notes). This technique is called “反竹”(fǎnzhǔ), which is perfect for higher range notes and glissandos. Musicians often have several different sets of hammers to choose from, all with slightly varied tones.

Another hammer variety is the “雙音琴竹” (shuāng yīn qín zhǔ), which means “double-note yangqin hammers”. These hammers have the ability to play up to four notes at the same time, due to each single hammer having two striking surfaces on it. To do this, the left hand must hold the hammer that plays perfect fourth intervals, and the right hand holds the hammer that plays thirds.

shuāng yīn qín zhǔhammers. Floofa at the English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Music on the yangqin can be played either solo or as part of an ensemble. It can still be heard in some Cantonese music or the traditional silk and bamboo genre of the Shanghai region called Jiangnan sizhu. In an orchestra, the yangqin’s role is to play chords or arpeggios to add to the harmony. The yangqin is usually played right in front of the conductor due to its soft sound.

Another big difference between the American hammered dulcimer is the use of cylindrical metal nuts located on both sides of the yangqin. These are used for tuning of the strings (in addition to the tuning pins), but can also be used to slightly raise the strings to minimize any vibrations that are unwanted. Some varieties of these nuts come in a ball-shape, which makes them quick and easy to adjust, even in the middle of a performance. The player can incorporate portamentos (gliding from one note to another) and vibratos (pressing down on the strings) in this manner as they play.

Portamento can also be achieved with the use of a”滑音指套” [huá yīn zhǐ tào], which is a metallic ring worn by the musician and slid along the string. This instrument is also capable of harmonics and “顫竹” (chàn zhǔ), which involves flicking the sticks lightly over the strings, creating tremolo, a quick vibration.

Japan: darushimaa (ダルシマー)

Uzbekistan: chang

Korea: yanggeum (양금)

Mongolia: yoochin (ёочин or ёчин)

Vietnam: đàn tam thập lục (lit. “36 strings”)

Khim

Thailand: The khim was introduced to Thailand from the China yangqin, then to Laos and Cambodia. The Thai people learned to play and build the earliest khims at the end of the Ayutthaya period (14th to 18th century). It especially became popular alongside Chinese opera because it was used within opera groups. More recently, there was a rise in popularity due to a Thai novel Khu Kam (later a TV series and movie), where the main character played the khim, and more notably the classical Thai song “Nang Kruan”. This song is about the sadness of a woman.

The instrument is played with bamboo sticks which are flexible and have soft leather at the tip, allowing a beautiful soft tone. The khim is played either sitting on the floor, or sitting or standing with the khim on a stand. The 42 strings are brass, and have 14 notes (courses are in strings of threes). This is the standard size that is popular among beginners. The lowest note is ล (La2 or A2) on the left side of the bass bridge. The middle note is ล (La3 or A3) on the right side of the treble bridge. The highest note is ล (La4 or A4) on the left side of the treble bridge.

Butterfly-shaped khim. uraids, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

There are several shapes of the khim:

- Butterfly shape: This is considered the khim’s traditional shape.

- Irregular rectangle or trapezoid: This shape is used on bigger khim instruments, and is built for notes; either 18, 22, or 30 notes total. This shape is said to be easier for musicians to carry. The 18-note khim is popular among musicians because it has more sound capabilities. The 22 and 30-note khims are very large and therefore heavy. Typically only professionals play these instruments for special occasions.

- Oval: These are the most modern designs of the khim, known as a “fancy khim”. Like the original butterfly shape, there are 14 notes and 42 strings. It is often painted with a deep or bright color, and children who play like to decorate it with cartoon stickers. Due to its fun shape and colors, the kids often are attracted to this variety of khim.

The popularity of the khim is still on the rise.

Laos: khim

Cambodia: khim

It’s a Small World After All

As it turns out, there are many people playing the “obscure” hammered dulcimer all over the world! Tons of people just like you play the dulcimer, salterio, hackbrett, cimbalom, santur, yangqin, and khim. We are united by our love for hammered dulcimer music! If you’d like to learn more about the history of this amazing instrument, we recommend either Paul M. Gifford’s The Hammered Dulcimer or downloading this thesis The Dulcimer by David Kettlewell. We hope you have learned something new about the hammered dulcimer; either an interesting historical tidbit, or a new musical style that gives you the inspiration to pick up your hammers and play.

Please leave us a comment below with any questions, observations, or inspirations you’ve gotten from this post! Happy hammering!

About the author: In her childhood, Nicolette Foss could be found underneath piles of sawdust in her father’s hammered dulcimer workshop. She helped with odds and ends in the business, attended folk music festivals, and learned the importance of hard work. These days, you can find her belly dancing to instrumental Arabic music, learning the Serbian language, making short films with friends, and cuddling her cat Georgie. If you’d like to hire Nicolette for content writing or copywriting work, contact her at: nicolettelady@protonmail.com

About the author: In her childhood, Nicolette Foss could be found underneath piles of sawdust in her father’s hammered dulcimer workshop. She helped with odds and ends in the business, attended folk music festivals, and learned the importance of hard work. These days, you can find her belly dancing to instrumental Arabic music, learning the Serbian language, making short films with friends, and cuddling her cat Georgie. If you’d like to hire Nicolette for content writing or copywriting work, contact her at: nicolettelady@protonmail.com

Cover image: “File:Giovanni Battista Dall’Olio, Salterio in legno dorato e dipinto, 1764, Museo Civico di Modena, part.jpg” by Archivio del Museo Civico di Modena is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Tags: cimbalom, hackbrett, hammered dulcimer history, khim, salterio, santur, yangqin8 Comments

-

Marvelous, love the photos and videos as demonstrations, too!

-

Thank you so much for demonstrating the sounds of the different instruments and what type of music they play in various countries. Unlike the American HD, are most of the other instruments tuned chromatically?

-

Hi !

You can add another one : my pantaleon ! -

My great grandfather (William McNally) was a well known player of the hammered dulcimer and features in articles by Gifford and Kettlewell. My father still has his concert cimbalom made by Shunda and brought to Scotland in the early 1900s, alongside the hammers he used to play with. He maalso made his own musical instruments, including dulcimars and small harps.