February 17, 2023

By Nicolette Foss

Oftentimes, when people hear the word “dulcimer”, they automatically think of the narrow-bodied zither whose fretted fingerboard is plucked or strummed. Well, this ain’t it!

The hammered dulcimer is often confused with this more well-known zither, which is called the mountain (or Appalachian) dulcimer. And while they are both zithers played in the folk music world, that is where the similarities end. How’d they end up with the same name? Nobody knows, but in this article, we are going to let the hammered dulcimer have its day in the limelight.

You’ll learn the anatomy of the hammered dulcimer, how it’s played, a bit about its rich history, and answer the oft-asked question: “Is it hard to play the hammered dulcimer?”

Ready? Let’s get hammered!

Hammered Dulcimer At a Glance

The Lady Victoria plays hammered dulcimer.

The hammered dulcimer is also known as “hammer dulcimer”. The word “dulcimer” was originally Graeco-Roman and means “sweet song” (Latin “dulcis” means sweet, and Greek “melos” means song).

The hammered dulcimer is a trapezoid-shaped stringed instrument played with wooden mallets called “hammers”. The hammers strike the strings that have varying diameters, tension, and positioning, creating different sounds. The sound resonates behind the wooden soundboard, making sweet, ethereal music.

There are typically two strings grouped to create each note. This is called a course. The more strings per course, the louder the sound. While most American dulcimers usually have two strings per course, it is possible to have one string per course (like our Fledgling one-string version). But variations of the hammered dulcimer can have up to eight strings per course!

The hammered dulcimer player either sits or stands with the instrument in front of them, and beats the hammers against the strings in a percussive fashion. Traditionally, it was played on the floor with the player sitting cross-legged (which is still typical of those playing the santoor). However, most modern American players use a hammered dulcimer stand to support the instrument as they sit in a chair or stand.

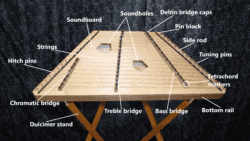

Anatomy of a Hammered Dulcimer

Hammered dulcimers come in all different sizes. Some can be more rectangular, and some may be more trapezoid. Most will have two bridges, while some of ours can have three or even four bridges. Typically, the bigger the instrument, the more notes it will have. This means you can play even more songs.

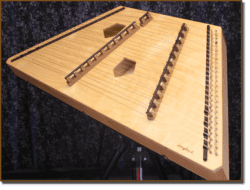

Here is a picture of our Phoebe Chromatic hammered dulcimer, which has three bridges:

Let’s dissect the anatomy of the hammered dulcimer.

- Hitch pins: These small pins are where the strings are originally hooked, to secure the tension that will be provided by the tuning pins.

- Soundboard: This is the surface of the dulcimer that the sound the strings make vibrates against. How the soundboard is constructed will enhance the power and quality of the hammered dulcimer’s sound.

- Strings: Flexible material that holds under tension, causing it to vibrate and create sound and music. Typically strings are made of steel, but can also be made of brass, nylon or gut (literally comes from animal intestines!), or a combination of materials. The varying diameter of the strings contributes to higher and lower notes.

- Sound holes: The holes in the soundboard help enhance the sound of the music. This happens by the vibration of air volume inside the instrument and near the holes. Typically, the hammered dulcimer’s sound holes are in the front, but most of our models have sound holes in the back.

- Delrin bridge caps/Delrin rods: The black rods on top of our bridges provide a resting place for the strings to keep them from wearing into the wooden bridges.

- Pin block: The block of wood that is part of the frame the pins are buried into. This block holds the pins and must be made of a specific kind of wood so the pins aren’t too tight or too loose.

- Side rods: These black rods just before the hitch pins and tuning pins stop the strings and create the vibrating string length.

- Tetrachord markers/bridge marks: These white marks on the bridge indicate the tonic note where the scales start. You can think of them as marking the “boxes” on the dulcimer, which signify specific keys and chords. They will also help you find your place since all the strings look the same!

- Tuning pins: The pins on the end help you tighten or loosen the tension of the strings. If your instrument is “out of tune”, it is time to adjust these pins! To play a nice-sounding instrument, you will need to learn how to tune (don’t worry, it’s easy).

- Treble bridge: The bridge in the middle of the dulcimer holds all the higher notes.

- Bass bridge: The bridge on the right side of the dulcimer holds the lower notes.

- Chromatic/extended range bridge: Some dulcimers include extra bridges, like this one. It holds a combination of missing chromatic notes from the other two bridges. At times, some of our instruments also include a fourth bridge, which we call the extended range bridge. Having these extra bridges will allow you to play more of certain music genres, like blues, jazz, and classical music.

- Bottom rail: Along with the top rail, this rail helps form part of the frame structure that connects the pin blocks.

- Dulcimer stand: Most modern dulcimers are played on a hammered dulcimer stand, which props up the instrument for easy-access playing.

When perusing hammered dulcimer products, you’ll probably come across confusing numbers such as 13/12 or 15/14/7/6. The numbers are included in the names of the dulcimers and they refer to the number of courses on each bridge.

The first number represents how many courses are on the treble bridge and the second number represents how many courses are on the bass bridge. Some dulcimers have extra bridges (like the Phoebe Chromatic featured in our anatomy picture). On our dulcimers, the 3rd number represents the courses on the chromatic bridge. If there is a fourth number, that represents how many courses are on the extended range bridge (Our Finch Chromatic Pro and Swift Compact Chromatic have extended range bridges).

So for example, 13/12 refers to a dulcimer with 13 courses on the treble bridge and 12 courses on the bass bridge. 15/14/7/6 indicates 15 courses on the treble, 14 on the bass, 7 on the extended range, and 6 on the chromatic bridge.

The Swift Compact Chromatic hammered dulcimer is a 15/14/7/6.

How to Play the Hammered Dulcimer

The hammered dulcimer is played by using hammers to strike the strings to the left of the bass bridge, and the strings on the right and left of the treble bridge. If there are other bridges, their notes will be struck on the side of the bridge opposite the nearby pins.

In the US, hammers are usually held lightly between the thumb and index finger. The player lets the hammer bounce on the string, preferably an inch or so away from the bridge. Hammers are typically made of wood, but can be made of many different materials, and made in a variety of styles. Using the bare wooden edge of the hammer will provide a sharp tone. Other hammers that are wrapped with cotton, felt, or leather will have a softer, more ethereal tone.

A wide variety of musical genres can be played on the hammered dulcimer, including Celtic, folk, old-time, bluegrass, waltzes, reels, jigs, hymns, pop, and yes, even metal. Songs played are usually limited to those in the major keys of C, G, D, and A, which are the sharps keys and their relative minors. It would be possible to play in flats keys, (F, B flat, etc.) but the note arrangement would be completely different, so most of us don’t. If you know how to transpose keys, this can easily be done!

Sound complicated? Watch Chris demystify the hammered dulcimer:

A Brief History of the Hammered Dulcimer

There are several theories as to the origin of the hammered dulcimer. Most commonly, it is believed that the hammer dulcimer originated in Persia around 900 A.D. The instrument is more than likely related to one of the early models of the psaltery of those days.

We estimate this dulcimer to have been created in 1850’s New York.

After its possible conception in Persia, the dulcimer was then said to have arrived in North Africa. And sometime between 900 and 1200 AD, the Spanish Moors and returning Crusaders brought it to western Europe where it was popularized. The Roma people then carried it along in their caravans to eastern Europe. Either the Europeans or Persians brought the instrument to China, where it spread to countries like Thailand and Korea.

From Europe, it made its journey across the ocean with the American colonists in the early 1700s.

As you can imagine, this world-traveling instrument is still found amongst the folk traditions of all the countries it has touched. And although still somewhat obscure, the common sound and folk history unite us. These hammered dulcimer variations throughout the world are known by the names of salterio, hackbrett, cimbalom, santur, yangqin, and khim (yet there are still more variations out there!). We enjoy learning about these traditions and blending and incorporating them with our own.

Is it Hard to Play the Hammered Dulcimer?

This very old instrument may seem complex. We are often asked, “Is it hard to play?”

Not at all! The way we look at it, we are all hardwired to make music. All you need is passion, patience, and persistence! You will find that learning the hammered dulcimer can be very intuitive, and if you are drawn to it, you will start learning chords and then playing your favorite songs in no time.

If you have no previous musical experience, the progress may be slower, but it will still be fun! What is important is not how good we get, but that we are enjoying playing and learning. Then we improve naturally!

There are also many experienced and patient teachers and free video lessons to help you along your way. We find it most helpful to first learn where the “boxes” are on the dulcimer (Chris touched on this in the previous video). This will help you easily get oriented on where the notes are. Once you’ve done that, you can move on to learning scales, then playing simple chords and chord progressions.

Teacher Jess Dickinson expertly explains in this video lesson where “boxes” are on the hammered dulcimer:

How Much Does a Hammered Dulcimer Cost?

The 13/12 Chickadee hammered dulcimer

Sound like fun? It is! But how can you buy one? You may think buying a hammered dulcimer will be pricey. But while some models definitely can be expensive, other models are much more affordable. We aim to provide instruments that everybody and anybody can have access to!

For beginners, we recommend getting a more simple hammered dulcimer with two bridges to start. That would be a 13/12 Chickadee (currently $374), or the most simple 9/8 Fledgling one-string model (currently $199), or the two-string model (currently $273).

If you are looking for a more full-range dulcimer, we recommend a 17/16/8 Phoebe Chromatic (currently $774) or a 17/16/8 Finch Chromatic (currently $1,050).

Creating Music for the Ears and the Soul

Now that the hammered dulcimer has had its day in the limelight, you can see that although somewhat obscure, this instrument has a lot of heart, history, and variety. And learning the hammered dulcimer can be fun, and ultimately rewarding in many ways.

The community is full of fellow musicians who get enjoyment out of creating something delightful for our ears (and souls!). We see the hammered dulcimer community as one big family, who are willing to support and help each other learn to create beautiful music.

Interested in learning more about the hammered dulcimer and being part of this wonderful community? Drop us a comment, contact us, or join the active and helpful Hammered Dulcimer Players group on Facebook!

About the author: In her childhood, Nicolette Foss could be found underneath piles of sawdust in her father’s hammered dulcimer workshop. She helped with odds and ends in the business, attended folk music festivals, and learned the importance of hard work. These days, you can find her belly dancing to instrumental Arabic music, learning the Serbian language, making short films with friends, and cuddling her cat Georgie. If you’d like to hire Nicolette for content writing or copywriting work, contact her at: nicolettelady@protonmail.com

About the author: In her childhood, Nicolette Foss could be found underneath piles of sawdust in her father’s hammered dulcimer workshop. She helped with odds and ends in the business, attended folk music festivals, and learned the importance of hard work. These days, you can find her belly dancing to instrumental Arabic music, learning the Serbian language, making short films with friends, and cuddling her cat Georgie. If you’d like to hire Nicolette for content writing or copywriting work, contact her at: nicolettelady@protonmail.com

2 Comments

-

Where in the NY (city, long island) area would you go for lessons ?